How Napoleon Could Have Won BEFORE Waterloo

Strategic Errors during the Waterloo Campaign

INTRODUCTION

The door of history turns on very small hinges. I think it was in Tolstoy’s War and Peace that I first read about the idea that random, tiny occurrences can subvert macro historical forces. A series of accidents, of little mistakes, coincidences, are enough to pivot the course of history away from any predicted historical outcome, and Waterloo was no exception — on 18 June, on those unremarkable fields of Belgium, history turned on a dime.

I at least have heard the following too many times to count: ‘Napoleon could not have won at Waterloo’, ‘Napoleon was out of his prime by 1815’, ‘the French army of 1815 was far from its heyday’. Maybe, but look at the days preceding the battle and one cannot help but be impressed by his persistent talent. What if I told you that Napoleon never wanted a battle at Waterloo in the first place? The fact that it happened already represented the downfall of his plan…

My aim here as an amateur is just to explore and hopefully provoke some thought into the strategic occurrences that played into the emperor’s ultimate defeat.

LAST FLIGHT OF THE EAGLE

Napoleon in 1815, returned from Elba, was not what some would have us think. He was not a cynical, aged general past his prime. The Northern France ‘Waterloo’ campaign testifies to the opposite: that he had retained his genius.

The restored emperor had around 125,000 troops for this campaign. Unlike with his young conscript ‘Marie Louises’ of 1814, Napoleon in 1815 had recruited his Armée du Nord exclusively from veterans. These were good, loyal troops.

Stationed in Belgium were two Coalition armies: that of the Duke of Wellington (Arthur Wellesley) 107,000-strong and that of the bellicose Gebhard von Blücher with 123,000 Prussians — 230,000 men total. Both were of inferior fighting quality. Wellington described his men as the “scum of the earth” because, for one, his was a mongrel army composed not just of British but of Hanoverians, Nassauers, Brunswickers, and Dutch, and, for another, much of it was second-rate militia. This was also true for Blücher, as most of his army was Landwehr.

N.b. then that Napoleon in 1815 was presiding over a military situation far superior to that of 1814, when he pulled off a brilliant defensive campaign despite the massive concentration of the Coalition against him.

Stakes were high. Napoleon in June 1815 had chosen not only to attack a larger force but needed to win decisively to have any chance of peace talks. Defeat would see him off to the final resting place: St Helena.

The military situation may have been better, but politically it was worse off. Much manpower was dispersed due to royalist uprisings. As was his custom, nonetheless, Napoleon sought to export domestic insecurity to the battlefield and resolve it there, at which point no one at home could much question him.

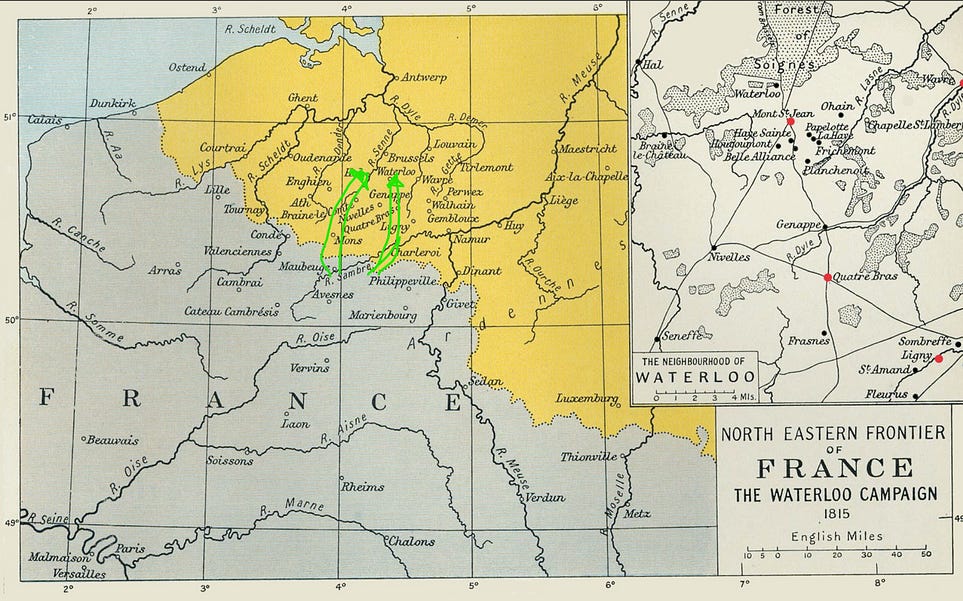

Historian Stephen Beckett II writes of two operational plans that Napoleon drafted in anticipation of the campaign. We can call them the ‘Mons Plan’ and the ‘Charleroi Plan’ (as HistoryMarche on YouTube termed them). The goal was to divide-and-conquer the two allied armies and sweep into Brussels (capital of modern-day Belgium); these plans represented the two routes that Napoleon could take.

See above (in my crude green arrows) the respective trajectories of the Mons and Charleroi plans. Beckett speculates that the Mons Plan was a ruse; its orders were uncharacteristically imprecise for the meticulous Napoleon, while the Charleroi Plan was decked out with impressive detail — which was closer to the Emperor’s modus operandi. Either would probably have done what he was really trying to achieve: the execution of the signature position centrale (central position) strategy, whereby, in a form of defeat-in-detail, the French army would insert itself in-between two distinct enemy forces (when both forces combined would outnumber the French one). While a portion of the French would hold off one force, the majority would be defeating the other. Once achieved, the French army as a whole could recombine against the enemy remnants, winning two battles where one battle would have returned defeat.

Another typical element of Napoleon’s strategy was speed: the French corps were to stealthily concentrate on the Sambre and be ready to advance by 13 June, taking the Coalition by surprise as they lounged in the Low Countries. Remember: the Anglo-Allied and Prussian armies were unsuspecting, and their troops were scattered around Belgium. Hence this method, tried-and-true, should have delivered the swift decapitation of the Coalition armies.

But what one can expect, from theory alone…?

Blunder No. 1: Soult as Chief-of-Staff

Napoleon’s marshal Jean-de-Dieu Soult had always been a trustworthy general on the field. At Austerlitz, he had led the French attack that brought about Napoleon’s greatest victory. But he had no talents for being a chief-of-staff. That role demanded administrative skill, not tactical skill.

By contrast, the man with whom Napoleon had the most synergy was Louis-Alexandre Berthier. Take Napoleon’s word for it:

“There was not in the world a better Chief-of-Staff…”

“In my campaigns, Berthier was always to be found in my carriage... Berthier would watch me at work, and at the first stopping-place or rest, whether it was day or night, be made out the orders and arrangements with a method and an exactness that was truly admirable. For this work he was always ready and untiring. That was Berthier’s special merit. It was very great and valuable, and no one else could have replaced Berthier.”

So Napoleon’s chief of staff could manage a complex, byzantine staff system that just worked, but anyone else would struggle to comprehend it. Unfortunately, Berthier died three weeks before Waterloo… I’ll omit details here, but they’re suspicious enough that people wonder whether he was murdered or committed suicide — jury’s still out.

Bereft of Berthier, Napoleon did not have many options. He should have chosen Louis-Gabriel Suchet as replacement. Suchet and Davout (more on that later) were two of the finest officers out of the five marshals Napoleon still had, only five out of the 26 Marshals of the Empire he had once possessed. Suchet had experience as chief-of-staff and Soult could have been leading one of the wings of the army in the place of someone like Emmanuel de Grouchy.

Quoting Alfons Libert’s opinion:

“[Napoleon] sent Suchet to Lyon to protect the Piedmont border. Certainly an important task in 1815 but subordinate to the invasion of Belgium. Suchet would have been a far better chief of staff than Soult.”

How exactly did Soult trip up? Well, to start with, he went to the wrong place and did not receive orders in the proper order. The result of this was that Soult confused himself. The Armée du Nord was subsequently ordered to march on Mons, not Charleroi. When Napoleon caught wind of this, he had to send out orders again to correct the direction, delaying the French advance from the 13th to the 15th. Keep in mind that in such a tightly-planned operation such as this, every day mattered in terms of maintaining the secrecy and executing the surprise. He still hoped that the invasion could be kept a secret. But alas French traitors alerted Gneisenau, chief of Blücher’s staff, of the impending attack at midnight on the 14th. The Prussians had been graced with 12 hours of the night to prepare and field an army at Sombreffe. The British would follow thanks to the coverage from Prussia.

“Without this treason committed by members of the French army, the surprise intended by Napoleon would have been successful to an even stronger degree than was the case now.” — Lettow-Vorbeck

Assuming that no mistakes would follow on the French side, we can say: had Napoleon’s advance begun on 13 June and not two days later, no significant Coalition force would have been able to prevent a forced march to Brussels. Wellington was in fact not expecting a divide-and-conquer thrust, but an envelopment by way of Mons, a rapid flank march to cut off his line of communications to the port at Ostende. As such…

“Napoleon has humbugged me, by God; he has gained twenty-four hours’ march on me.” — Wellington

Imagine the result without the delay and without the treachery. Prussia’s I. Korps would have been brushed aside. In the dead of the night, Napoleon’s crack troops would be on a loaded march to Brussels. The army would occupy the Nivelle-Namur road; thus the Coalition in Belgium would be split…

In the event, Napoleon’s plan to disrupt the coordination of two allies collapsed; on 16 June, Wellington and Blücher literally met in person! Instead of having to fight no battles, Napoleon would have to fight two.

We cannot blame Soult too much here. Napoleon was the one who appointed him; the general was merely performing his duty to the best of his abilities. So Napoleon may have complained:

“If Berthier had been there, I would not have met this misfortune.”

But the misfortune was begotten and borne of himself.

Blunder No. 2: Ney’s Errors

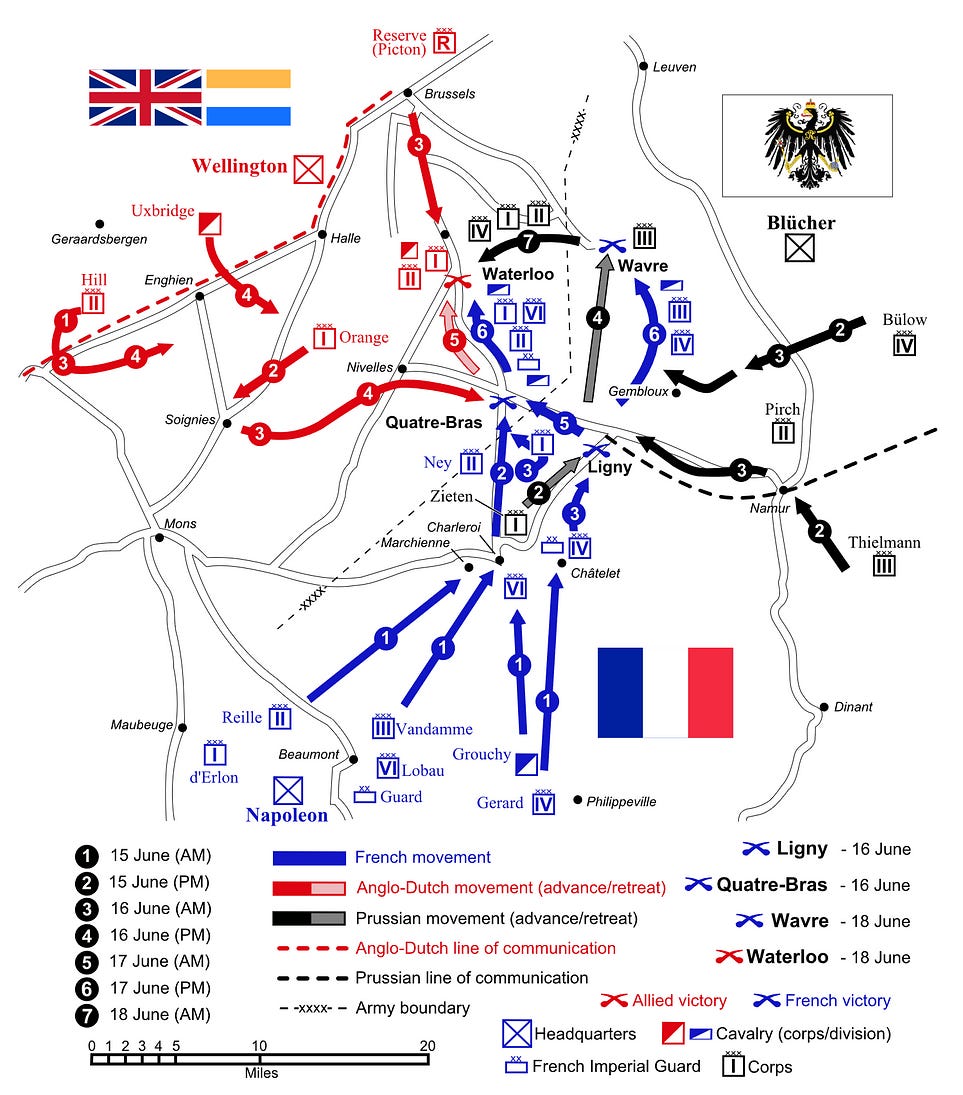

We realise now that Napoleon was going to face two enemy armies at two separate battles.

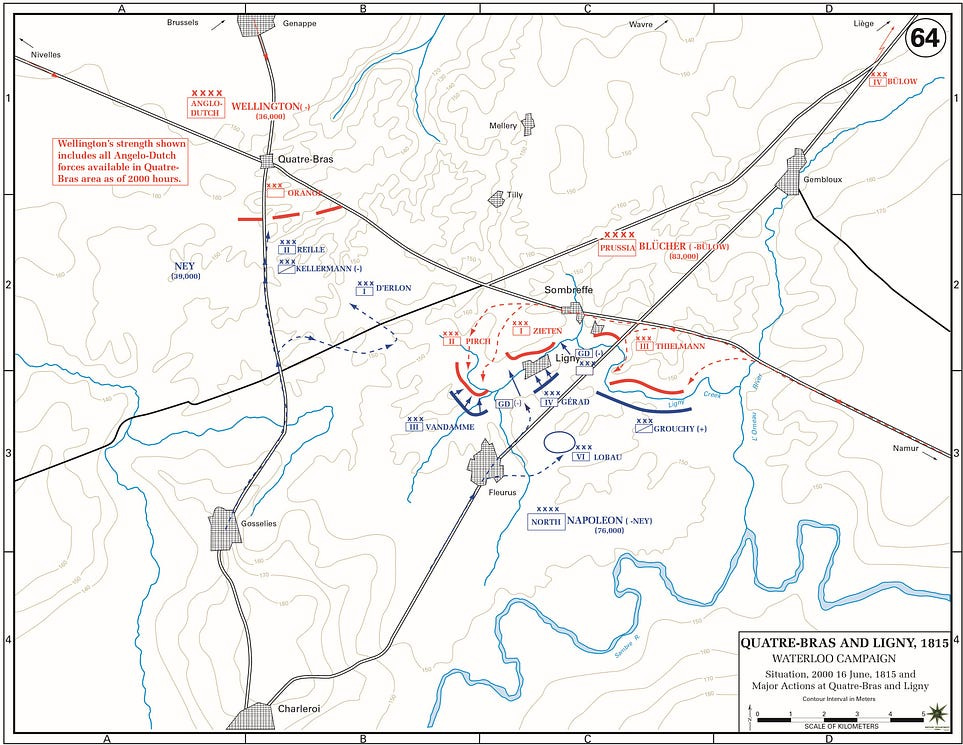

On the 16th, the two wings of the French army fought at Quatre-Bras against the British and Ligny against the Prussians. Napoleon was at Ligny, while Marshal Michel Ney led the attack on the vital crossroads at Quatre-Bras. The orthodox historiography of the latter battle is to say that it was a French strategic victory, even though tactically Ney lost to Wellington, since Wellington was prevented from coming to the aid of the Prussians at Ligny. Paul Dawson, however, challenges this view, pointing out in fact that Ney’s failure to capture the roads resulted in the disastrous inability of Napoleon to properly recombine his army before the final battle — Waterloo.

In an ideal world, Ney would have dislodged the Anglo-Allied army from Quatre-Bras and Napoleon would have attained a decisive victory at Ligny. Neither happened.

Before Quatre-Bras, Ney was not his normal self, feeling cautious rather than bold. Napoleon’s order (relayed by Soult) for Ney to seize the crossroads arrived before 11 AM on the 16th, but Ney prevaricated all the way until 2 PM; he had neglected to advise 1e and 2e Corps to prepare for an advance, which was necessary if the attack was to go ahead in a timely fashion. Over that period of tergiversation, Ney lost his 6:1 numerical advantage over the Prince of Orange’s men. No longer were they in his mercy. Consequently, he butted heads against ~34,000 allied men to his 20,000 — Wellington retained the junction by nightfall.

—

Napoleon planned for Ney, once he had won his battle, to be able to commit to the other battle going simultaneously, to demolish Blücher’s right flank: at Ligny. In his last victory, Napoleon beat 83,000 Prussians with 62,900 of his own, but the bulk of his enemy escaped in good order. The expectation was that Ney would have won by then, so Ney’s men could join Napoleon to deliver the customary coup de grâce of his ‘central position’ strategy. At 3.15 PM, Soult relayed a message to Ney telling him that the “fate of France is in your hands” and to attack the Prussians immediately.

As part of that, Soult ordered d’Erlon to march his 1e Corps agaisnt the Prussian right flank, to intensify a French tactical victory into a massive strategic one by routing the Prussians utterly. But just as he neared Ligny, d’Erlon received a new order from Ney; now he was to double back. By then, d’Erlon was too late to reach Quatre-Bras. Neither objective was realised as a result, and his corps had perambulated Belgium the whole day without turning the tide of either battle. (You can see this on the map just above: d’Erlon is winding around.)

Bernard Cornwell in his book (Waterloo: The History of Four Days, Three Armies and Three Battles) emphasises the historical consensus that Soult’s presence contributed to Napoleon’s defeat; he points out the existing animosity between Soult and Ney, being two prideful marshals — here, the ridiculous misutilisation of d’Erlon’s men is an example of the friction between them.

Blunder No. 3: Grouchy as Field Marshal

Ney as marshal had his ups and downs. Marshal Emmanuel de Grouchy was a whole other matter. He has copped a tonne of flak for his performance in the Waterloo campaign. Is it deserved? To some extent. Napoleon had promoted him to Marshal of the Empire and put him at the head of an entire third of the French army, 33,000 men, to pursue the Prussians as they fled the field at Ligny. If he could successfully tie them down, Napoleon would have a free hand to defeat Wellington at… Waterloo.

Grouchy had his work cut out, and the man may not have equalled the task. John Holland Rose (historian):

“Grouchy had hitherto held no important command. As a cavalry general, he had done brilliant service; but now he was launched on a duty that called for strategic insight. His force was scarcely equal to the work. True, it was strong for scouting, having nearly 6,000 light horse; but the 27,000 footmen of Vandamme’s and Gerard’s corps had been exhausted by the deadly strife in the villages [in the battle the day before] and were expecting a day’s rest. Their commanders also resented being placed under Grouchy.”

I recommend taking a read of this for an analysis of Grouchy’s actions, with the liberty to explore with more depth: https://www.napoleon-series.org/military-info/battles/1815/c_grouchyorders.html

But essentially, he received orders to pursue the Prussians relentlessly, putting a sword in their back. Grouchy and Napoleon were generally ignorant of which line of retreat Blücher would take. Grouchy made the assumption — though it proved false — that Blücher would be falling back all the way to Brussels to join up with Wellington. He was not aware that Wellington had taken up positions at Mont Saint Jean, which was a little north of the field of Waterloo.

In a limited way, Soult can be blamed again (according to Cornwell), as his orders to Grouchy were “almost impenetrable nonsense”, which the marshal misinterpreted entirely in the event. There are several more minor details for 18 June that military historians go over, ie his blunder in not advancing on two axes (including marching on the Dyle bridges) to spread a wider net for the Prussians, his traffic-retarded march from Gembloux, and the decision to pursue the Prussian rearguard all the way to Walhain and later Wavre. The most important problem was not one of these three. It was, rather, Grouchy’s lack of imagination. General Gerard was one of several who debated with Grouchy and tried to convince him, to no avail, to abandon the clearly outdated orders from Napoleon and Soult and to ‘march to the sound of the cannon’ — which had been heard not so far away with the beginning of the Battle of Waterloo. Gerard without question had the right idea:

“…The Prussian march had now definitely narrowed itself down to one of two alternatives, either they were marching on Brussels or else were moving to join forces with Wellington at Mont St. Jean. In either event, prudence and policy alike suggested the advisability of joining the Emperor as quickly as possible, for if the Prussians were moving on Brussels, they might be regarded as a negligable quantity in the battle at Waterloo. If, on the other hand, they were advancing to join Wellington, Grouchy, by marching on the cannon sound, would be most advantageously disposed to stop them, to hinder them, or to diminish the effects of their junction in the event of its having been accomplished.”

Grouchy was dogmatic and committed to the flaccid Battle of Wavre:

“My duty is to execute the Emperor’s orders, which direct me to follow the Prussians; it would be infringing his commands to follow your advice.”

The outcome thereafter was the one we know all too well.

Grouchy’s reputation has been absolutely dragged through the dirt, particularly by French historians who favour(ed) Napoleon. His consistent defence was that he was following his emperor’s orders to the letter. Some new research regarding the ‘Bertrand Order’ issued to him is suggestive to the contrary — that Napoleon had actually given him more freedom than Grouchy professed. That order was actually buried by Grouchy for decades and has recently resurfaced. Napoleon himself did not hesitate to point fingers:

“Finally, I triumphed even at Waterloo, and was immediately hurled into the abyss. On my right, the extraordinary maneuvers of Grouchy, instead of securing victory, completed my ruin.”

But the blame game is never fruitful. The job of a commander-in-chief is also to make sure they select the right generals for the job. History buffs will always point to a readily available commander that Napoleon did not utilise! Louis-Nicholas Davout. The ‘Iron Marshal’.

Davout rests among the cream of the crop of the Marshals of the Empire. He met Napoleon in 1798, and there began a long and storied career, with Davout accompanying him in campaigns from 1805–1814 (Austerlitz, Jena-Auerstedt, Eylau, Wagram, Borodino, inter alia). It was at Auerstedt that Davout earned his fame. His single 3e Corps defeated the main Prussian army while the Grande Armée confronted a much smaller Prussian force to the south at Jena. Napoleon was so impressed that Davout was given the honour of entering Berlin first on 25 October 1806.

“At Jena, Napoleon won a battle he could not lose. At Auerstädt, Davout won a battle he could not win.” — historian François-Guy Hourtoulle

Davout was a beast on the battlefield. He could rise to independent command on any occasion. In Grouchy’s position, I surmise that he would have had no problem actually chasing down the Prussians after the Battle of Ligny. Grouchy was making the most of his experience; he could not trust himself to disobey Napoleon’s prior order. Davout was more imaginative.

So where was he? Napoleon had appointed him Minister of War, and during the Northern France campaign Davout was busy gathering troops in Paris. History would be quite different if Davout was there; but given that Napoleon had never expected to fight battles at Quatre-Bras, Ligny, or Waterloo — and that we know it was only bad luck that denied him a total victory — the emperor did not see his presence as necessary.

CONCLUSION

“Had it not been for the desertion of a traitor, I should have annihilated the enemy at the opening of the campaign. I should have destroyed him at Ligny, if my left had done its duty. I should have destroyed him again at Waterloo if my right had not failed me.” — Napoleon

The 1815 campaign exists in parallel to Napoleon’s other feats where he was dogged by more numerous opponents and called to use genius as his force multiplier. Let’s say one or two or even three of the errors listed in this article were not committed. We might take a victory for the French to be assured. But here History is a double-edged sword: even if these factors were changed, at any moment some moment of chance (leaked orders, a blunder on the field, a stray bullet) could have subverted the historical outcome. If there’s any take away here it is that even the most ‘assured’ historical courses are not truly so: structural forces act, as well as intentional ones, but accidents determine how they are actualised.

Then we must extrapolate that historical course into the future. If the British had been pushed back into the sea and the Prussians smashed in the fields of Belgium, Napoleon would turn and prepare for a larger Russian and Austrian invasion — in our ‘timeline’, the front against the Coalition collapsed and the allies were advancing unchecked, but even so Napoleon was clinging to the hope of a concerted national resistance. About 150,000 from the National Guard or new youth who had come of age could be called up; Davout was gallantly preparing the defence of Paris; in fact, he had gathered a force larger than Schwarzenberg and his Austrians; Grouchy was returning after his action at Wavre; in spite of Waterloo historically, France assumed the war would continue.

Thus, in a world where Napoleon did prevail over the Coalition in Belgium, it is not likely that people now would not be thinking that the War of the Seventh Coalition was an inevitable French defeat. It would have been pretty morbid, to be sure, and an uphill road for the emperor resurgent. But nothing’s impossible in history, which is at once our great torment and our great delight.

REFERENCES

These are not rigorous citations, apologies in advance.

For the OOB: https://decisiongames.com/wpsite/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Waterloo-OB.pdf

Opérations de l’Armée du Nord: 1815, l’analyse by Stephen M. Beckett II

Campaigns of Napoleon by David Chandler

[A video that presents most of the above in amazing fashion]

https://www.napoleon-series.org/military-info/battles/hundred/c_chapter2.html

https://www.napoleon-series.org/military-info/battles/hundred/c_chapter3.html

https://www.napoleon-series.org/military-info/battles/1815/c_grouchyorders.html

Marshal Ney at Quatre-Bras by Paul Dawson.

The Life of Napoleon I: Including new materials from the British official records by John Holland Rose

what is this, some advice? yea no i'm still probably going to end up committing these errs